THE COLOUR OF ORDINARY DAYS: STUDIO GHIBLI

~ Vanshikaa Khandelwal and Aditi Kakade

TY, B. Sc. Economics

Reading time: 9 minutes

The true spell of Studio Ghibli is not cast in fantasy, but in showing us that the ordinary, when seen with care, can be extraordinary. The films carry an overarching philosophy of life to cherish small wonders, find meaning in the everyday and show you how there is peace in slowness. Iyashikei (癒し系), meaning healing, is the genre most Ghibli movies fall under. We see characters living slowly in their daily mundane tasks, asking us to look upon our lives kindly as we follow suit. It is a kind of catharsis to our minds, that makes one reassess what is truly important in this life. Ma (間) in Japanese is a concept involving the use of space to enhance an artwork. The actions of characters are designed not to advance the storyline, but to make us feel with the characters and interpret the tone of the movie emotionally, and individually with these feelings, instead of telling us what to think in a narration.

According to one observer, the beauty in Studio Ghibli’s world lies in “curiosity” – characters lose themselves in the exploration and appreciation of their surroundings. Japanese culture often values mono no aware, an awareness of the transience of life and a tender sadness at its passing. The storytellers (Miyazaki, Takahata and others) show that even in a troubled world, “there are good things and …wonderful ways of experiencing and looking at the world.”Another thing that is observed in Ghibli movies, is the use of colours to set the tone of the movie. Each movie follows its own palette and makes the audience feel like they are a part of the world with the vibrant colours.

Ponyo is a story about magic and chaos. A goldfish princess is befriended by a human boy Sosuke, who names her Ponyo. She longs to be human, and breaks out of her wizard father’s home, spilling dangerous elixirs and potions that wreck havoc on Sosuke’s town. A tsunami warning is issued, bringing a stressful tone to the film as Ponyo seeks shelter with Sosuke and his mother in their home. Surprisingly, the very next scene is Ponyo, Sosuke and his mother take a good five minutes to cook and eat ramen and warm milk with honey. At first, I was really confused with the pace of these scenes. Why, in the middle of this crisis, would there be such an intimate and cozy scene? Did the characters not realise the pace of the events around them?

I was so used to Western media making every plot point an advancement in the story, that I genuinely started to think babies would stop waves as high skyscrapers. The more I thought about it, it started to make sense. Ghibli didn’t play into Western patterns, and the point Miyazaki was trying to make was exactly what I was questioning. The pauses make you think about the simple joys in life- the warmth from a hot meal made with love, the smell of honey, the joy of being young and seeing things from a lens of innocence, safe under your mother’s care, protected, no matter what was happening outside her arms – this is the tone created in this scene. The ramen had no consequence to the story. The honey didn’t give Ponyo special powers to save the city. The kids were allowed to remain kids and enjoy a moment of calm even in the crisis going on.

The film gently reminded me that I am allowed to enjoy peace amidst anything going on in my life, at any given time. The ocean is bathed in blues but it turns muddy green when Ponyo escapes. Ponyo herself is a warm, red character against this backdrop, showing her as a lively force of nature, full of love and curiosity. Sosuke’s home is a safe place for the kids and we feel it in the warm yellows and earthy tones. The contrast in the surreal, glowy magical world and the pastel human world shows Ponyo’s inner struggle of picking one over the other. While Ponyo shows comfort in familiarity, Spirited Away shows growth in unknown situations.

Spirited Away is a story of believing in yourself as we see Chihiro, the main character, grow through adversities. Chihiro and her parents are moving to a new town and find a strange tunnel along the way. They go in to explore it and find huge fields and a town. Unaware of the magical nature of the town, her parents sit to eat the food mysteriously laid out at a restaurant, but are turned into pigs as dark spirits come to visit the town for the witch, Yubaba’s bathhouse. Fighting to turn her parents back to humans, Chihiro finds herself working in this spirit realm under the cruel Yubaba. The spirit world is filled with bright reds and bright lights, threatening, but still inviting. Scenes in the bathhouse are red and gold, showing excess and greed, and the scenes with spiritual entities have a glow around them (steam maybe?) that evokes the magical nature of this place. Chihiro herself is surrounded by shadowy colours in her moments of confusion and distress that evolve to soft blues, oranges and pastels, as she grows.

A textbook Ghibli moment is when Chihiro’s friend Haku brings her some onigiri (rice balls) and the movie stills to show her eating and slowly crying as she realises the predicament she is in. It is a raw moment that forces us to grieve along with her. Never once does it shame her or us for feeling helpless – in fact this is seen as a turning point for her character, it celebrates human emotion and resilience. Another good example is her train ride along the flooded plains with the spirit ‘No Face’ towards the end of the movie. They watch the water glide with the train and the sun reflect off it in silence – evoking a deep sense of reflection, and I found myself thinking about the whole journey Chihiro has been through and how much she has grown. This is one of the most famous scenes from this movie, praised for expressing more in silence than words could.

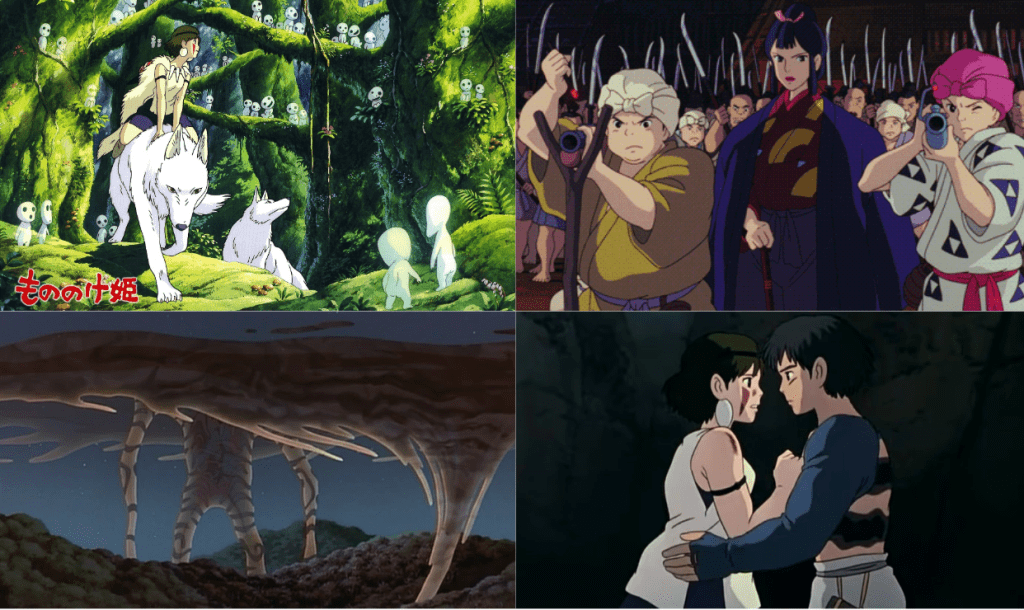

Princess Mononoke is a story of nature and preservation. Ashitaka and San, from different worlds, come together to save the forest San lives in. The film is fully immersed in forest and earthy tones of greens and blues, with a stark white contrast seen in forest spirits, Kodamas, and the wolves of the forest. Humans are seen as the destroyers of nature. Here, there is a deliberate silence and slow pace when introducing nature and divinity, like when Ashitaka enters the forest or the Shishigami (God of the Forest) appears. We become so used to the earthy hues of the forest, that when the colours change to show artificial colours like greys and bright reds, we are as perturbed as the animals living in the forest. The jarring use of muddy brown and purple overcomes the screen when the humans injure the Forest Spirit and fill us with as much sadness and gloom as San. Ashitaka and San’s bond is seen in the wordless scenes where they tend to each other’s wounds, or sit together.

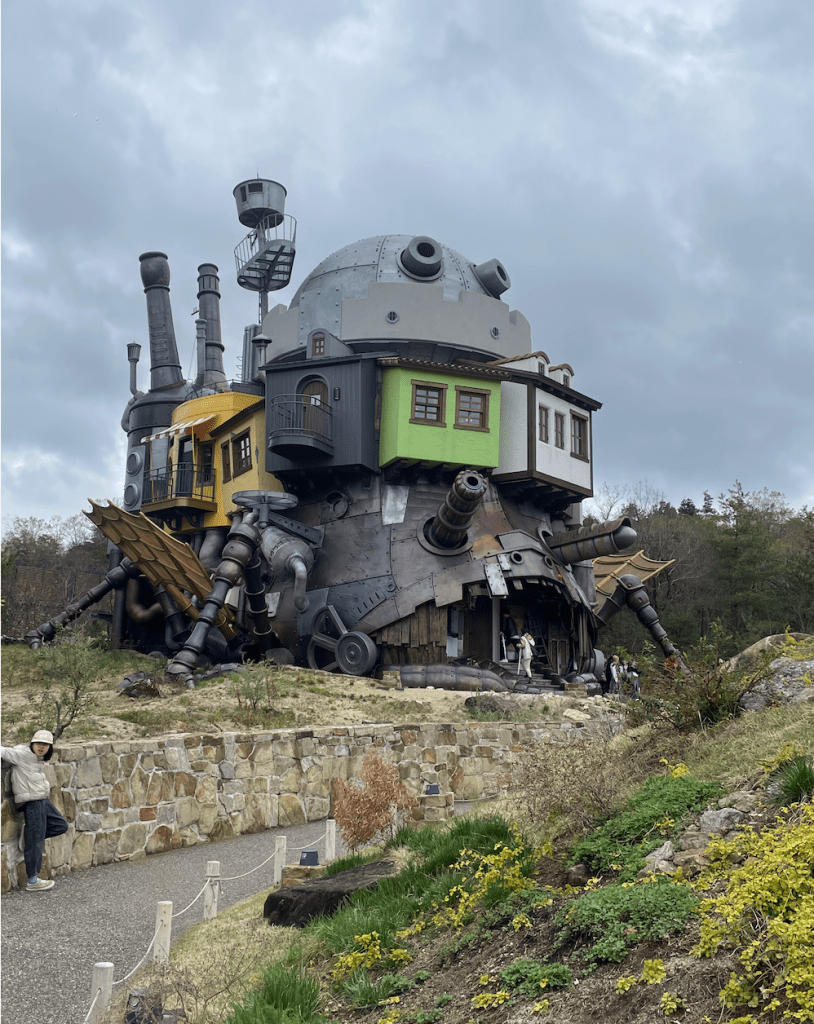

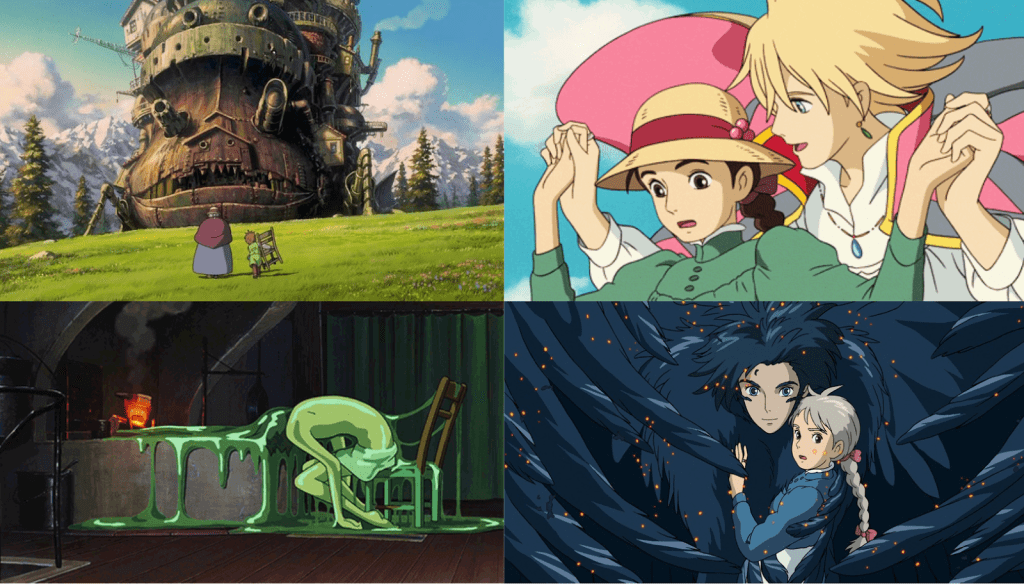

In contrast to the natural hues, Howl’s Moving Castle (my absolute favourite) is a story of magic and love. Howl is a notoriously powerful wizard, and Sophie is a hat-maker. After he rescues her, she is cursed by his rival and turned into an old lady, unable to reveal her identity or the curse put on her to anyone. She leaves her home and with nowhere to go, comes across Howl’s Moving Castle, a castle made of scraps and metals, dull, dusty and dimly lit on the inside. She hires herself as housekeeper and we see the colour come back into the house as the fire shines brighter. Any scenes involving magical encounters are brightly coloured. Howl himself is shown as an ethereal being, always loud and colorful. Even when he has a mental breakdown over his hair colour because the dye was changed (we love a diva), we see dark but vibrant colours. As Howl overuses his magic and starts to turn into a monster, his ethereal colours fade into black feathers and we feel his whimsy disappear.

Ghibli’s rich imagery and heartfelt stories inspire creativity far beyond the cinema hall. Educators have documented how viewing Ghibli films sparks artistic responses: in one study of college students, participants “composed a wide variety of creative projects” inspired by what they saw on screen. This kind of imaginative engagement is echoed in fan communities everywhere. Industry commentators note that Studio Ghibli’s “distinctive aesthetic – soft colour palettes and intricate details has long served as an inspiration for artists across the globe.” The cozy, fantastical worlds and emotive characters encourage people to draw, write, craft cosplay, and even compose music in tribute. Indeed, many fans say watching Ghibli films feels like planting a seed of creativity. As one writer observes, “watching a Studio Ghibli work can feel as if the germ of an idea has taken root, swelling inside of us.” In other words, these movies do more than entertain; they gently unlock something in us that yearns to create.

Aspiring artists and storytellers often cite Ghibli as a formative influence. The blend of wonder and humility in the films shows how imagination can be grounded in everyday life. Ghibli’s art style from the lush forests to the bustling bathhouse of Spirited Away has inspired digital artists to try replicating its magic. Filmmakers and animators likewise credit Miyazaki and Takahata for teaching the value of detail, hand-drawn craft, and narrative heart. Since Ghibli stories balance adventure with tender moments, they suggest to viewers that even small acts of creation – a sketch, a poem, a song – can capture big emotions. They show that observing the world closely and imagining beyond it can lead anyone to dream up new possibilities.

If Ghibli teaches artists to dream, it teaches the rest of us to pause. Juggling is the most important skill one can have in today’s world. With the job market the way it is, the AI revolution and the concept of “gig economy” being front and center, if you can’t juggle learning, working, and improvising, life will roll away from you. It is imprinted into us from our school days where we juggle multiple subjects, tuitions, sports, music and other activities our parents force us to get into (seriously, like why was I in Lego classes?). It’s okay when you’re fooling around as a child, but when you grow, your choices start becoming a life-altering level of serious. I felt like I was in a race and I ran and ran and ran and obviously got burned out, but the weight of stopping or slowing down was so crushing that it forced me to move despite it all. I felt weak for feeling tired or being frustrated. The first time I saw a Ghibli film, I could breathe. It was a reminder that, in a life built on constant juggling, slowing down is not failure. I stopped feeling like taking time out to do small tasks that make me happy was a loss. I was proud of myself for the work I had done and the race I had run, but I no longer needed to be breathless, I would be just fine at my own pace.

Whether it’s rain gently falling in long takes, clouds drifting in slow motion, or trees swaying now and then, Miyazaki takes us through the ordinary. Ghibli suggests a slower pace: watch fireflies flicker in the dusk, listen to crickets in a mountain meadow, and feel the creak of the wooden floor. As one analyst notes, in the midst of the changes, the directors wish to demonstrate “that there are indeed things in this world that are beautiful, important, and worth fighting for.” We see this in Castle in the Sky and Arrietty, which acknowledge life’s “eternal flux” (the ongoing cycle of growth and decay). Princess Mononoke’s cursed wolf spirit laments, “Life is suffering… the world is cursed. But still, you find reasons to keep living.” Rather than offering easy escape, Ghibli movies portray reality’s bittersweet edges. The payoff is a quiet optimism: as one curator sums up, the animation itself “tells us visually that life is an unmissable ride of worthwhile experience.” In the end, Ghibli’s gift is not escape, but the gentle reminder that the colour of our ordinary days is enough.