Between the Gallows and Glory: Meeting Caravaggio’s Magdalene

Dhrithi Mijar

B.Sc. Economics (2025-2029)

Estimated Reading Time: 6 minutes

When someone is a fugitive with a death sentence hanging over their head in the early seventeenth century, most people would lie low, change their name, and maybe work on the violent tendency to brawl with strangers that got them condemned in the first place. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio instead gave the world one of the most scandalously beautiful images of spiritual rapture ever rendered on canvas.

At first sight, you would not be able to guess the tumultuous circumstances under which Caravaggio’s illustrious Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy was created. I most certainly did not. When you walk into the dimly lit hall of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Bengaluru, knowing that what you are about to lay eyes upon is the first original Caravaggio to be brought to India, your senses are suddenly heightened almost to a level rivalling Spiderman’s. The low thrumming of the humidifier is the first indicator: this is an irreplaceable four-hundred-year-old painting that could be tarnished by human breath. The undertones of other gallery visitors shuffling around is broken by the thump-thump-thump of every step on the wooden floorboards, terribly out of sync with your even louder heartbeat. Every inhalation of meticulously regulated cool, clinical air tells you the amount of care taken by two countries to make this display possible. Slowly, your eyes adjust to the darkness, lingering deliberately over every placard detailing the man’s life and his work of art, preparing to see the painting itself.

I could caption the painting as “Me after I submit an assignment one minute before the deadline”, but I simply can’t bring myself to. Sometimes art leaves you with a certain speechless reverence — I felt it when first I gazed at the intricate Hoysaleswara temple carvings in Halebeedu, where all you can think is ‘how did they DO that?’. I am not being dramatic in the least when I say that getting to see the actual-genuine-for-REAL Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy knocked the breath clean out of my lungs. The partially reclining figure of Mary Magdalene is a testament to the realism Caravaggio is hailed for, capturing the otherworldly experience of listening to the celestial harmonies of angels.

Unlike his contemporaries, he chose to portray a more grounded version of divine entrancement: there is no levitating Mary, no overtly symbolic divine ray of light or halo, no descending angels. Mary Magdalene is painted in all her flesh and blood, her strength and vulnerability alike seeping through the canvas. An almost imperceptible tear wells up in her eye; her hands clasp in tension; her mouth parts in divine revelation and bliss, her lower lip swollen and tinged green. This transmission of humanness through the figures in his paintings is what made Caravaggio controversial in his time, with some of his religious paintings rejected for being too radical by those who commissioned him.

Image Source: Photo by Author

Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy itself was rediscovered only in a private European collection in 2014, believed lost, and its existence known only through reproductions. Despite all the nuance it exudes, the artist leaves much about it ambiguous—where is Mary Magdalene sitting, really, engulfed as she is in darkness? Is she actually experiencing ecstasy, or is it grief and pain in her expression?

Though they shared the same first name, Michelangelo Caravaggio was not the Michelangelo— Michelangelo Buonarroti of Florence. Both were named after the archangel Michael. But while Michelangelo typified his lofty artistic ideals as a model for all artists to follow, Caravaggio tended to the saint’s more turbulent nature. The man was notorious for roaming unkempt, dressed in all black with a sword and spoiling for fights at the slightest provocation. He was popular as a talented artist and attracted influential patrons— despite the often questionable moral nature of his paintings and having a criminal record running several pages long with assault, harassing the police, and complex affairs with courtesans.

In 1606, his long-drawn feud with a wealthy man called Ranuccio Tomassoni culminated in a duel in which the opponent was fatally stabbed. It is speculated that the fight was over a tennis match, but the motive behind the fight remains unclear. Whatever the reason, he was convicted of murder, and a bounty was placed on his head, encouraging anyone who recognised him to carry out the death sentence for a reward. During his time fleeing, he produced many acclaimed paintings in exile, including Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy. Even with the lilting subtlety in the subject’s emotion, the painting does betray some of the urgency and agitation that the artist himself must have felt. The long folds of Mary Magdalene’s cloak are rendered in wide, vigorous brushstrokes that turn at the end. Critics attribute this characteristic style of painting to him, but the rare speed and determination seem especially evocative here.

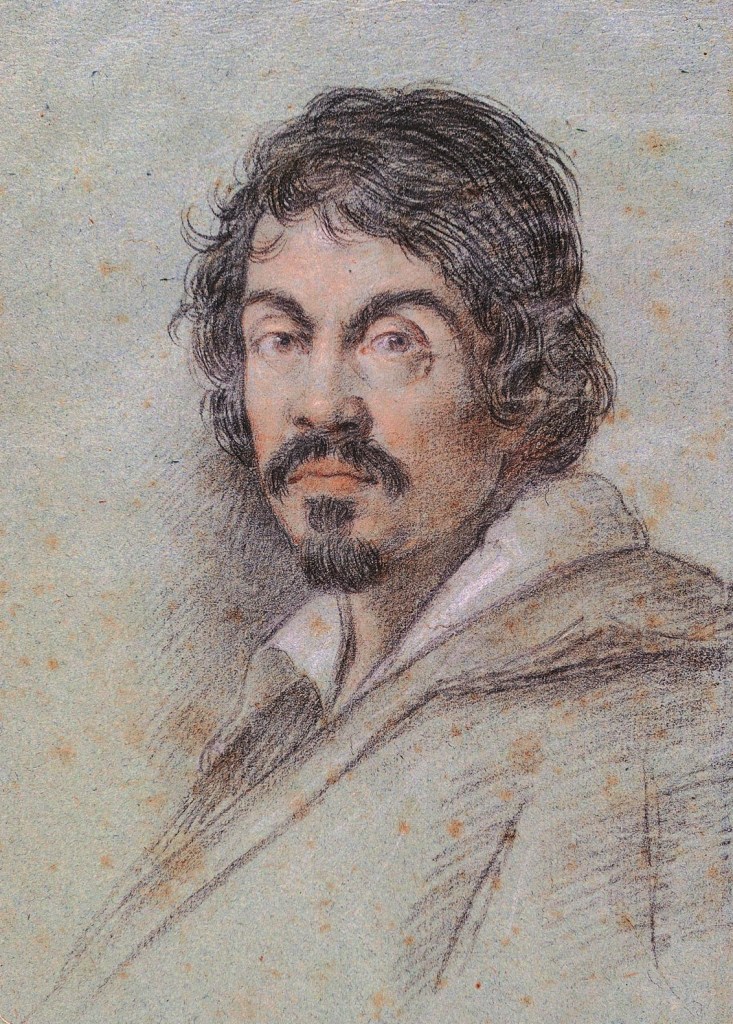

Image source

The face of a man who woke up and chose violence, and painted masterpieces as a side hobby.

With the painting lit by a solitary light placed strategically to its top left, the technique of chiaroscuro could be appreciated in all its glory. This pretty word refers to the pronounced contrast between areas of light and dark within an artistic composition, originating from the Italian words chiaro, meaning “clear” or “light,” and scuro, meaning “dark.” An offshoot of this style called tenebrism (from the Italian word tenebroso for ‘dark, gloomy, mysterious’) is credited to Caravaggio who employed it extensively. The inverted values of light and shade in the painting can be observed in the eye sockets, nose, ear and fingers especially, with a sort of irregularity that does not follow any form but rather allows the variation to express a new reality of the human figure, unifying it without depending on idealised anatomy.

The main subject of the painting grasps all attention immediately; most people usually miss out on noticing the smug juxtaposition on the canvas of the cross and skull. Facing the viewer is a wooden cross at the top left with a crown of thorns that seem to pierce through the painting itself, almost tangible. And at the bottom right below Mary Magdalene’s elbow is a dark skull that appears to be disintegrating.

Most of Caravaggio’s life is shrouded in mystery, being intense but cut short at thirty-eight years by death due to debated causes in 1610, still on the run. While born to a well-off family, as a young boy he lost his father and grandfather to the bubonic plague outbreak and lived in poverty for much of his life. For someone who made so famous the use of the light and the dark, Caravaggio himself evidently tended towards the dark. Tenebrism, after all, is the form of chiaroscuro where darkness is the dominating feature. A cardinal’s secretary once wrote of The Grooms’ Madonna, which had been painted by the artist for a small altar in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome (and removed after just two days):

“In this painting, there are but vulgarity, sacrilege, impiousness and disgust…One would say it is a work made by a painter that can paint well, but of a dark spirit, and who has been for a lot of time far from God, from His adoration, and from any good thought…”

Caravaggio’s was a life riddled with deaths, crime and violence in an eternal pull between chiaro and scuro, between the cross and the skull, between good and wickedness, undone by himself until the oil paints could salvage nothing in his life unlike the saints they created, certainly not his own freedom.

In the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde wrote, “To reveal art and conceal the artist is art’s aim.” Where cancel culture today sparks the never-ending debate of whether we can separate the art from the artist, one can’t help but wonder if being awestruck by an artist’s accomplishments is appropriate in the light (haha) of their personal infamy. Perhaps Caravaggio, in his work abounding in the divine and making use of theatrical techniques, was after the same end: art that speaks in its own voice. Centuries later, his works hang not in the shadows but in the spotlight, inviting us to take in their rapture and ruin. The man who ran out of time left behind an immortal vision of salvation that still endures. One can’t deny, though, that it was pretty iconic to give his contemporaries a run for their money whilst being on the run for murder.