Game’s Over (For Now)

Nitya Kakade

SY B.Sc. Economics (2024-28)

Estimated Reading time: ~4 minutes

Most people spend decades dreaming about retirement, picturing a laid-back life and a lifetime of vacations. And almost all of them would be old and grey before they see any of those dreams come to life. Athletes, meanwhile, are in a different league of their own.

It’s well-known that an athlete’s peak performance is when they’re somewhere in their twenties or thirties. While the age of retirement varies widely across sports, it’s usually much lower than an ordinary office worker. Most athletes retire in their 30s, although in some cases athletes can play professionally until their fifties. However, those who can play that “late” in life are the exception rather than the norm. So the window to succeed, both in terms of performance and income, is very small and increases pressure on the athlete to secure financial stability quickly.

About 90% of players need to find work after finishing sports to maintain their financial security. But surprisingly, the biggest reason for this isn’t insufficient earnings from sport – it’s their financial decisions. Some players find themselves making poor or overly risky investments and bad purchases. Many even say that they have a lack of business acumen, or received bad advice from financial planners.

It may be insane to think about, but around 60% of NBA players go broke within five years of retirement, and 78% of NFL players go bankrupt or are under financial stress just two years later due to unemployment or divorce. These are the people playing national leagues in the USA; they earn millions of dollars in their few years playing professionally. It’s all in their hands, but where does everything go wrong? Players foolishly trust relatives or close friends with money, with no idea what is happening, only to find it rapidly depleting one day. The money’s not even safe with professionals – in fact, at least 78 players lost over $42 million in total within just three years because they trusted their money with financial advisors who had questionable backgrounds.

Unfortunately, some people bring about their own ruin. Antoine Walker earned $108 million in his 13-year run with the NBA. That’s a life-changing amount of money, especially for someone coming from humble beginnings. But guess what? He filed for bankruptcy only two years later in 2010. This was because of his gambling debts and failed real estate ventures.

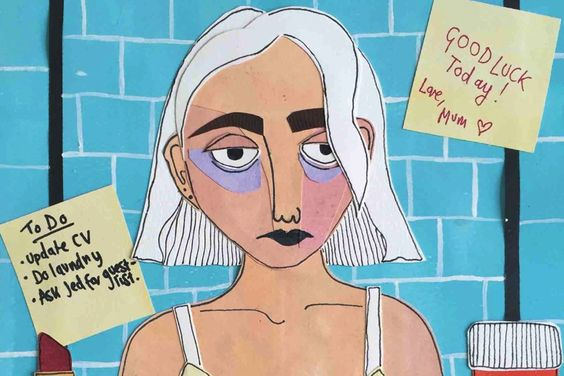

Financial distress is just one of the few problems athletes face post-retirement. Even if their finances are in order, the shift in lifestyle often creates a sense of dreariness in some people. Retired players are more likely to have common mental disorders (anxiety, depression, distress and addiction) than those currently playing. This can be due to many reasons, such as having to retire involuntarily, dissatisfaction with their career, changes in body perception, health issues and loss of identity.

It must be devastating to leave behind something all of your life has revolved around so far. One day you wake up and remember that you have no more matches left to play, and then you think blankly, “Now what?” This is a common feeling among many athletes. Once you’re used to the adrenaline rush that comes with playing a sport, nothing else can fill the void that comes after the end. India’s tennis champion Sania Mirza described feeling empty after her last match. All of a sudden, she had no training or gym to attend, no fixed schedule to follow. It’s hard to reconcile with changes to a routine you’ve built your whole life around.

An athlete’s retirement transition depends a lot on how they’ve programmed their own mindset, so to say, and how that connects with the nature of their termination. Athletes whose sense of identity and self-worth are closely tied to their sport are particularly prone to feeling dissatisfied with their career, and find it hard to adjust to their new reality. On the other hand, athletes who create a healthy sport-life balance over their career find this transition much easier. Developing other interests and making contingency plans for life after sport are important things players should take care of.

But what if everything is going right, when the player suddenly faces an abrupt end to their sporting career? Athletes who are forced to retire due to injury, finances, skill or personal issues may find it hard to cope with the regret and loss, and it may be hard for them to bounce back.

Mary Carillo was one such player, with a short-lived career in tennis. She won the French Open for mixed doubles in 1977. Because of a knee injury, she had to retire just three years later in 1980 at the age of 23. But she didn’t let that deter her. She went on to be a successful tennis analyst; most notably working for CBS, ESPN, PBS and NBC. Carillo earned a “career Grand Slam” for covering the Australian Open, French Open, Wimbledon and US Open, and even won two Peabody awards for co-writing sports documentaries.

So maybe life after retirement isn’t all so bad. Remember Antoine Walker from earlier? One might think that bankruptcy is the end, but Walker turned over a new leaf and recovered within two and a half years. Today, he teaches athletes how to manage their money and avoid the struggles he faced.

Some athletes go on to be even more successful after shifting to a different field entirely. Famously, Dwayne Johnson (🤨🪨) used his wrestling fame to pivot into a Hollywood career. He was even the highest-paid actor in the world for five non-consecutive years.

All of these examples show that the story doesn’t end when the lights go out. Retirement may feel heavy and overwhelming, but it opens the door to new opportunities, and athletes might find fulfilment in entirely unexpected ways. Some stay close to the sport they love, and some take new paths. What matters is that the discipline and resilience they’ve developed over the years of competition don’t retire along with them.

This game might be over, but the next level is waiting. And for many, it turns out to be even more rewarding than the first.