The Roman Lasagna of Ruins

Gargee Dixit

TY Bsc

Estimated Reading Time: 8 mins

A Roman Underground Metro Station

Source: original

A couple of years ago, I had the opportunity to live out my Percy Jackson dream – a chance to visit Italy! My 14-year-old self was jumping up and down, exploring the ruins and walking through the places where Heroes of Olympus occurred. But travelling around the city as a tourist also exposed me to the problems of the common man, and now I have the economic backing to yap about it. (Thank you, Urban Economics!)

You see, ancient cities, which are the ultimate fantasies of any archaeologist, are also incredibly hard to develop in terms of urban planning. In towns like Rome or Athens, archaeological discoveries aren’t a novelty; they are simply a part and parcel of any major construction project. Rome is literally nicknamed “the Lasagna City” as the historical ruins are stacked one after another like a lasagna. Due to periodic flooding of the Tiber River, natural sedimentation occurred over pre-existing structures. During rebuilding efforts, construction materials were reused, and city planners, until the 20th century, even made a conscious choice to build on top of the ruins – creating the “lasagna effect” that we see today.

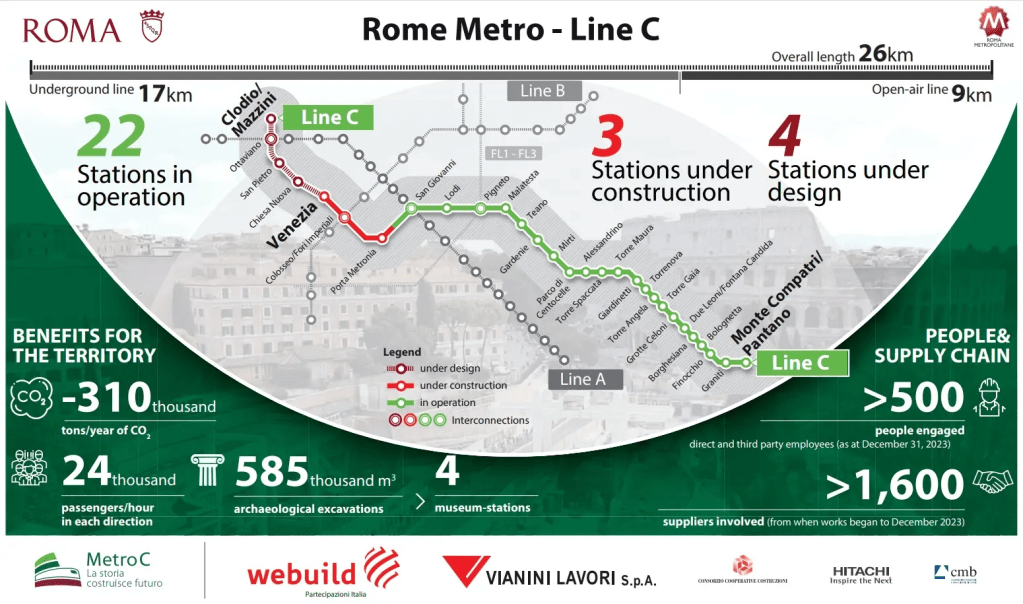

This all came to a head when the construction of the subway line C started in Rome. Mind you, this project has been under construction since 2006, and it is still not completed. The subway line is a 26km line aiming to connect the north-eastern parts of the city to the southwest, passing through the heart of the city – the Colosseum, and the Venezia, which houses ‘Altare della Patria’ or simply the Wedding Cake Monument. These monuments (to be honest, the entire city of Rome) are a world heritage site, so constructing this metro line was a behemoth, gargantuan task.

As the majority of the construction of the metro was underground (17/29 stations are underground), a large parcel of land near the historical city centre was dug, and lo and behold, a huge number of archaeological ruins were found! Around 5,00,000 archaeological findings were excavated while constructing this metro line, and even active excavation sites were opened. Around 40 excavation sites were opened while working on this project, and there’s an interesting regulatory framework behind this. The metro construction was done in tandem with the Italian state and the Roman city supervisory bodies. The Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape is the primary legal framework which deals with the ownership and management of archaeological ruins. According to this law, any movable pieces like statues or artefacts, and even immovable ruins of the city, are ipso facto the property of the state of Italy. Superintendents appointed by the Ministry of Culture are local officers tasked with approving construction sites in the country. If any ruins are found during construction, the work is halted or adjusted to accommodate the archaeological sites. This makes the task of building underground metro lines too tedious and a regulatory nightmare.

As the planned metro line was slated to go through the city centre, the urban planners expected to find archaeological ruins. To deal with this problem, the urban planners relied on two solutions. Four Tunnel Boring Machines (TBMs) were used during construction. These specialised machines operate deep underground, thus skipping a lot of “layers” of Old Rome. They are low-impact and cause significantly less vibration, which helps maintain the quality of the soil. The second trick the planners used was creating barriers around the excavation sites through crosswalls (semi-permanent concrete walls enclosing the site) or freezing the soil around the site to provide support. These crutches support the sites while the construction of the metro tunnels is completed. The planners had to walk the thin line of preserving their heritage and avoiding the bloated cost that comes with tiptoeing around the city’s past. Literally. The total cost of building this line C has reached up to 3.47 billion euros, with 70% of the funding coming from the central government, while just 18% comes from the city’s municipal corporation. This hefty price tag makes me wonder, does it make sense to build a metro with such high, bloated costs?

Aside from the positive externalities associated with an increase in public infrastructure, historically, Italy has performed poorly when it comes to transportation. It ranks 22nd out of 28 in Europe for its efficiency in the transportation sector. A study in 2019 found that 80% of the Italian population relied on private vehicles as their primary mode of transportation, while only 0.8% relied on metros. Even freight transport is primarily carried out via roadways, leading to lost time and economic inefficiencies. Especially in urban areas, metros provide the fastest, economical, and most environmentally friendly way of transporting large numbers of people. Developing a robust metro system is not a suggestion; it is a requirement (even India is finally catching up!).

Urban development in cities like Rome and Athens, which have so much history just buried underground, is a tremendously hard task. These prehistoric cities are a major hub for tourism. Their major export is tourism, leading to inflated costs of living in their CBDs (central business districts), which are, by nature, their prehistoric city centres. Unlike a normal city, the firms and households in these cities have to bid not just against their own population but also against incoming tourists with disposable income and commercial activities in and around the centre. Such competition has led to increased urban sprawl around the city of Rome, where locals who are outbid (or, because of legal archaeological reasons, simply can’t bid on state property) relocate around the periphery of the city and obviously rely on private transport to travel to and from the CBD.

Burdened with its glorious past, cities like Rome seem to be bogged down by the weight of their own history. Upkeep and maintenance of archaeological sites is expensive, even discovering them slaps a hefty bill, and Romans stumble upon old ruins during any major construction, like an annoying ghost hellbent on hindering your development. But these ruins are the drivers of economic growth. Last year, around 215 billion euros were injected into Italy’s economy through tourism. That is 10.5% of their GDP! Lugging around the weight of its past is no easy feat, but they seem to be trying. A lot of archaeological sites found during the construction of the metro line were incorporated into the station itself. Nicknamed the “Museum-station”, some of these discordant structures found harmony, housing a small museum in the metro station. The first of its kind was the San Giovanni station along the same Metro Line ‘C’.

This kind of harmonious integration of Rome’s historical legacy demonstrates the very essence of Rome as an eternal city. It keeps changing, evolving and trying to accommodate its past while creating a foundation for its future. After all, as the poet Tibullus said in the first century CE;

“No matter what empires rose and fell or what other changes occurred in the world, Rome would endure and continue to stand.”